Decked out in brand-new waders, wearing a vest stuffed with fly boxes and clutching a shiny new rod and reel, you stand ready to test your passion for fly fishing and make the first cast on the rocky edge of a pristine trout stream. Mentally, you review the checklist. Correct rod and line weight for the size of the stream and potential trout? Check. Fly dangling from the right size tippet matching color and size of the insects near the creek? Check. The appropriate stealthy approach so as not to spook skittish trout? Check. But wait, where to cast? You vaguely remember from either a casting lesson or guidance from a buddy the offhand comment that the first cast is the most important since, if perfect, it has the best chance of fooling fish and, if not, might spook the entire pool. Confused, you gaze at the infinite possibilities obscured and muddled by rocks, hurried currents, and gently splashing white water…

Relax. Recall the old saying, “10% of the water holds 90% of the fish.” Finding the magic 10% is made easier through understanding the basic structure of a stream. That knowledge allows you to eliminate dead water and find the perfect target. Those who transitioned from spin to fly might instinctively know where trout lurk based on years of experience. However, flipping a fly presents a unique challenge driven by achieving a drag-free drift. Plunking and cranking a heavy spinner through a likely holding spot requires less thought than carefully placing a weightless fly where the current vagaries and line management mechanics come into play.

At the most fundamental level for new anglers, a stream consists of three primary features: riffle, run, and pool. While the perfect stream features a riffle transitioning into a run and terminating in a pool, nature prefers a more random approach and may connect them in any order. Riffles range from inches to a couple of feet deep, characterized by white water splashing over a mixed rocky bottom. A change to a more moderate gradient usually produces a run. Runs are deeper and bumpy with less (or no) white water, have a visible, strong current, and may flow over any bottom structure. As the gradient flattens, runs spill into pools where the current slows and deep water prevails, usually in the middle of the pool. Depending on the stream, the depth of each feature is relative. Riffles on a mountain stream may be inches deep, transitioning to a foot deep run terminating in a pool no more than two or three feet deep – measurements scaling with stream size. Regardless of the setting, the critical characteristic is the current speed and the subsurface structure – does it offer trout feeding positions solving the energy equation while providing safety?

Trout are experts at assessing the number of calories burned to obtain food versus calories gained in eating a morsel. In the perfect trout world, they would sit in still water, requiring no energy to maintain position while slurping food drifting gently in the water column. In reality, the current pushes food, forcing trout to interact aggressively, snatching morsels as they bullet by. Therefore, trout need areas of relative calm adjacent to current where they can bide their time, expending little effort, before darting into the streaming buffet line. Knowing this removes most of the stream as a casting target. Just follow the current and identify contiguous placid water. Typically, where there is no current, there is no food, although trout may hold there when not feeding if those positions offer greater safety.

Dr. Robert Bachman discovered different species of trout are comfortable with varying current speeds. He determined brown trout prefer slower current (up to two feet per second) while rainbows can manage faster water (six feet per second). In a 1980 study, Wesche determined brookies prefer even slower water moving at half feet per second. Knowing the trout species, reject parts of the stream where the current is outside the preferred range. However, in making that calculation, recognize current runs at different speeds in the same vertical slice. In his book, Moving Water: A Fly Fisher’s Guide to Currents, Jason Randall documents that the “lowest 20 percent of the water column has a velocity approximately 50 percent of that of the fastest current near the middle of the vertical water column.” Accordingly, there may be a sweet spot below swift water depending on depth, something to consider as you reject spots.

Since trout are not at the top of the food chain, the ones who survive are safety experts. They seek water deep enough to offer a layer of protection from predators over structure compatible with their natural camouflage. Riffles runs and pools provide different solutions. In riffles and runs, the surface is ruffled and bumpy, limiting the ability of predators, ourselves included, to see through changing glare patterns. At the other end of the spectrum, the surface of a pool may be perfectly calm and slick with perfect visibility all the way to the bottom. Given the protective glare in riffles and runs, trout do not require as much depth to achieve safety while in a pool they will be in deeper water. A general rule of thumb is that trout need at least a foot of water to feel comfortable in a riffle or run, and, even then, there has to be a safe area nearby.

So… where do you flip the first cast in a riffle, run, or pool? Best to explain using pictures to avoid thousands of words.

Riffles

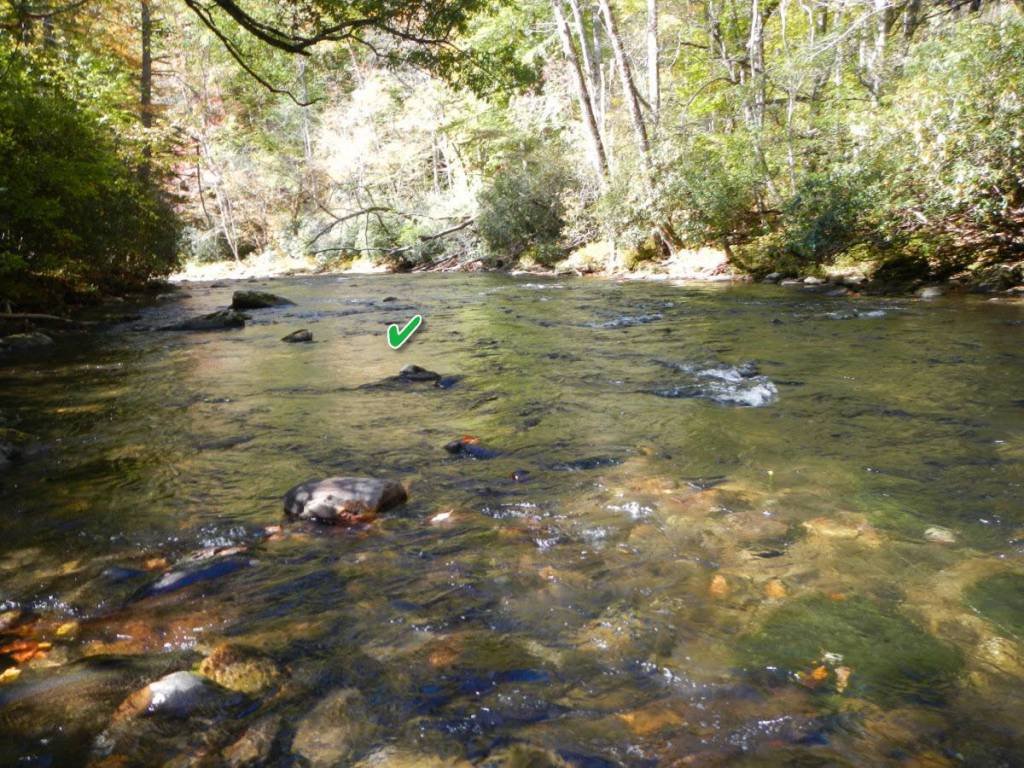

This is what an aggressive riffle looks like and is closer to being a rapid. These are hard to fish due to the fast water swirling around the rocks, but even a rapid can be fished if it is deep enough. Riffles and rapids hold trout where the water appears slick on the surface, lacking the turbulence of the surrounding white water.

The checkmarks show likely areas where the turmoil subsides and trout may hold. But these are still rough spots and, if the riffle is shallow, there may not be a protected position in either location. A better bet is to look to the left near the large rock.

The rock blocks the swift current and creates a large slick extending to the left. It has visibly deep sections protected from the flow, terminating in a ledge with what appears to be a protected dark overhang at the far left (following picture), providing additional required safety.

Cast upstream of the rock where the flow will sweep the fly at the edge of either current seam (seams shown as red lines) through the slick. Generally, it’s a bad idea to cast a nymph or a dry fly into the turbulent water just behind a rock since the current is troubled as it struggles to stabilize. Better to throw a little bit upstream and quickly mend the line so the fly moves naturally. This allows you to cover any feeding position at the front of the rock. If the bottom structure is compatible, large rocks create a subsurface pillow of calm water to their front.

The following picture shows an easier, more typical riffle to decode. The rock near the checkmark blocks the current flowing along the right-hand edge. The sizeable downstream slick provides a safe resting location within easy reach of food pushing with the current. How do you know a spot is “safe” when looking at it from a distance? Unless the water is noticeably darker, indicating depth, or you see a protected area under a boulder, you will cast blind. In the end, there are two ways to determine if a spot is good. The best is to catch a fish. The alternative (that many anglers fail to do) is to walk over to look at it after fishing it – the only way to get to know a stream in detail.

Part 2 covers runs, banks, and pools.