It probably started during the January cold snap when temperatures plunged below freezing for several days. First, your spouse began to complain a little more than normal about the cold. Then you discovered the heat turned up a degree or two on the thermostat. A week or so later, your spouse forced you to watch “Beachfront Bargain Hunt” on HGTV because “there is nothing else on.” Brochures associated with renting beachfront property began to pile up in your mailbox. And, finally, your spouse made the direct appeal, reinforced by tearful, doe-eyed children waving beach pails, to go to the beach this year instead of the mountains. Poof! Your dreams of a vacation stalking wary brookies on rocky, joyfully gurgling streams disappeared in a heartbeat.

Don’t despair! Your spouse just did you the greatest favor of your life. Until you experience the adrenaline rush of a huge red drum ripping line out of a screaming reel, you have not lived. The southern coastline, from Virginia through Texas offers plenty of opportunities to tangle with red drum (also called redfish, reds, spottail bass or channel bass) and sea trout (speckled trout, specs): all lumped into the word “predator” for this article since it only covers the absolute basic basics and does not get into specifics for each game species. I highly recommend Captain John Kuminski’s book, Redfish on the Fly, for an in-depth tutorial. The Sportsman’s Best series of inshore books provides broader coverage of multiple species.

Most new anglers already have either a six weight rod for trout or smallmouth bass. Since saltwater predators eat the larger food, inshore fly fishing requires an upgrade to a heavier weight rod designed to efficiently throw the larger flies required to “match the hatch.” While some anglers stick with the six weight rod and work lighter flies, it is much easier to go big and use at least an eight weight, fast action (tip flex) rod loaded with a redfish or bass taper fly line to punch through the constant sea breeze. Floating line is fine but bring an intermediate sinking tip for situations where you need to push your fly towards the bottom faster in a strong tidal current. Do not use a full sinking line because oyster beds and other edgy bottom structure can quickly shred it. Be sure your reel has a good drag with plenty of backing since even a small predator has plenty of strength and energy to pull hard.

Use a strong tippet, either mono or fluorocarbon, with at least a 15-pound tensile strength. If you build your own leaders, minimize the number of knots since they will snag subsurface marsh grass as you strip.

Put away your freshwater flies, except for the big Clousers and poppers. Matching the saltwater hatch means selecting flies looking like baitfish (mullet, pinfish, menhaden and mud minnows) shrimp or crabs. Look for weighted flies tied on hook sizes 1/0 down to 4 with a weed guard. Grab a popper with a red nose and white body as well as a Dupre Spoonfly. As always, purchase flies at your destination to take advantage of local knowledge.

Since inshore species key on noise, flies can incorporate a rattle. I know this is heresy, but as a new inshore angler, you need the additional advantage scent provides until your skill increases. The ProCure brand seems to be a universal favorite offering scent variety ranging from mullet to blue crab. Put a drop or two on the fly to increase the odds of a hookup. Finally, since I have already been ostracized for suggesting scent, I may as well go one step further and recommend you bring your spin gear.

Why? As a new inshore angler, you have a learning curve to conquer. With spin gear, you can make more casts in a shorter period; using speed to find fish. Once you locate fish and learn what to look for, switch back to your fly rod. Besides, you may not have the skill to deal with a strong prevailing wind, so having a spin rod to fall back on protects your vacation.

Unlike lakes and rivers where the water level is stable, decoding the inshore puzzle requires an understanding of the impact of the tide on bait and predator behavior. Not surprisingly, the rise and fall of tide creates four different structure situations: high tide, rising, falling and low. To make the point, here are pictures of the same spot at different tide levels.

High tide:

Low tide:

Dramatic change! Each the situation requires a different approach. Although the picture looks the same at the middle of a falling or rising tide, the current flow changes where the predator will sit.

As Captain Allen Jernigan (breadmanventures.com) explained to me on a recent fishing trip into the shallow backwaters of the Neuse River basin, fish like structure. This is true regardless of whether the fish swims in fresh or salt water. The inshore structure consists of points, potholes, fallen trees, root balls, creeks, drop-offs, docks, and banks – no real difference from freshwater – with oyster beds, jetties, and tidal flats being the new features. Just like they do in fresh water, predator fish seek ambush positions where they are protected from something higher up the food chain.

Regardless of the structure, predators position downstream of the current flow, nose facing the current, in hopes of ambushing an easy meal being pushed along. For example, a predator will position on different sides of a point (in the eddy) depending on whether the tide is rising or falling and selects the optimum on time based on normal bait movement.

Here are some general rules to get you started.

At high tide, predators (except flounder) will be in the marsh grass away from the main channel. Key on the perimeter of open areas within the marsh grass rather than blind casting to random stalks unless you see redfish tailing. Look for baitfish movement on the surface to narrow your focus.

While many of high tide openings are easily visible from a boat, the best require movement up a creek since it provides additional organization to baitfish movement. Typically, creeks end in a wider “lake” where baitfish disperse and, of course, are followed by the predators. Fishing the creeks leading to these spots is always productive although navigation into the narrower channels is challenging (watch the tide level to avoid being stranded). In addition, they are easy to fish with fly gear given the need for stealth and finesse with a few false casts allowing precise placement of the fly.

At low tide, fish retreat to the channels and associated deep spots. Generally, predators are not active at dead low tide. A better use of low tide is to take the opportunity to get the lay of the land and locate the best places to fish during the rising or falling tide. In the case below, the main flow will be on either side of the tidal flat with the channel on the right and the point on the left becoming good places to target since deeper water is associated with both features.

When assessing a shoreline look for additional clues – all revolve around baitfish movement. In the redfish hot spot below, a creek feeds into a bay. When the tide moves out, baitfish migrate from hiding/feeding positions in the grass into the creek and follow the flow to the bay, continuing to move left with the tide. Predators position for this with the prime spot being marked by the “X” at a point just down current of the creek (side note – use Google imagery before you hit new water and look for likely spots).

Another way to locate good shoreline spots is to sit quietly and observe activity. As schools of baitfish scurry along the shoreline, there will be periodic “explosions” of surface activity as the smaller fish flee predators. Once you observe a topwater boil, fish that spot since a predator is present. Baitfish also tend to favor the lee shore (bank the wind is blowing towards), so observe that shoreline first. Another indicator is to pay attention to what the birds are doing. They hunt baitfish and where the baitfish are, predators will not be far away.

Generally, the best time to begin to fish a shoreline is when the tide hits the mud line, the break between grass and mud (shown). When the tide flows into the grass, baitfish follow, seeking cover. Predators also move inland to eat fiddler crabs. On the falling tide, predators wait in the channel or just within the grass line to snack on returning baitfish.

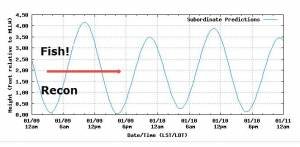

Everyone has a different opinion on which state of the tide is best while agreeing that the tide must be moving for maximum action. Determine the timing by reviewing a NOAA tide chart from a station near the area to fish (tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/tide_predictions.html). My personal preference is to fish from when the tide is half full to half low and poke around the rest of the time.

Once you find fish, the entry level technique can be boiled down into a few rules:

- Do not cast into the middle of a school, cast ahead or to the side

- Cast up current, let the fly sink. Allow the current to move your fly, stripping slower at first and then pick up speed

- When fishing a popper, do not stop stripping on a missed strike, continue to “flee” from the predator

No discussion of the basics would be complete without mention of a few of the unique safety aspects. Specifically, we are not at the top of the food chain and need to be aware of the danger presented by the American alligator and sharks. Neither of these should present many problems if you are aware of the possibility of their presence and keep any fish you are going to take home out of the water.

For sharks, it’s not a good idea to wade early in the morning or in the evening. Alligators rarely cause problems for humans, but you should not swim where they exist, minimize splashing and stay away from the banks where they may lie in ambush. This is especially important when females are guarding their eggs or young.

You are likely to find alligators in any coastal creek, such as the one below, between North Carolina and Texas.

It is easy to identify where alligators live by looking for crushed marsh grass adjacent to water. Many times, you can see their slides from the bank as well.

Bottom line: Put the mountain trout out of your mind and enjoy the coast!