Runs

The next picture shows a typical run. Note the ruffled surface as the stream adjusts to account for various sizes of rocks and boulders. Given the apparent uniform velocity of the current in most runs, they are harder to fish since the current, by itself, provides fewer clues. Generally, the current is faster in the middle than at the sides as a result of friction contributed by the banks and shallower water. However, as Randall noted above, depth overcomes speed, requiring careful evaluation of the entire span.

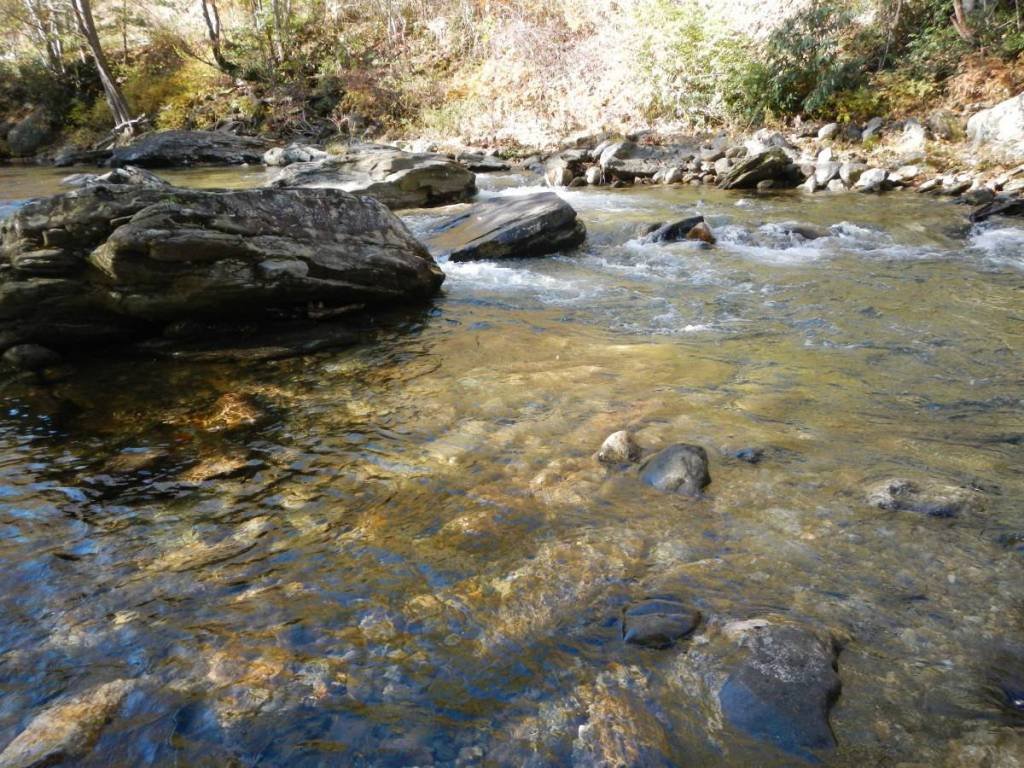

The transition between riffle and run (below) where the turbulent water of the riffle subsides into a fast, bumpy run is a great place to focus. Not only is the water deeper with plenty of subsurface boulders furnishing good, holding positions for trout (safety), but the availability of food is focused where the main current flows enter the run. Cast to the short channels between the large boulders (some, but not all, examples shown checkmarks).

Here is a more obvious transition location. The water below the large rock is visibly deeper, adjacent to a nice current flow and worthy of the first cast.

Looking a bit to the right, the second cast should go in the large slick created by flow on either side. Trout may be just ahead of where the currents merge (checkmark).

Runs on small streams are much easier to fish than a run on a large river since you can see all the choices. In the picture below, the run extends from bank to bank with glare providing additional camouflage. Assuming it is safe to wade, read the bottom of the run incrementally as you work it; looking for a light and dark pattern to reveal deeper cuts.

Clear water makes runs tough to fish. At first glance, the run in the next picture appears to be very shallow, merely inches deep. Unless you know that to be true as a result of a previous visit, do not ignore a spot like this! Instead, fish it carefully paying attention to the largest boulders since they offer the most opportunity for an overhanging ledge providing the safety needed to offset water clarity.

To prove the point, I waded into this run and took the picture below. The water is above my knee and offers plenty of protection given cracks, like the one under the boulder to the left of my foot, large enough to hide a nice trout.

Banks

A bank is always an interesting place to look for fish. Moving water carves out the soft soil of the bank to create good hiding positions close to the current flow. In this picture, taken in the same clear run shown above, the large rocks adjacent to the bank imply good ledges located in deeper water confirmed by a dark tinge not caused by shade.

Here is another example of a good bank holding position. The current flows into the cut below a large flat rock followed by a pool.

Pool

Anglers love fishing pools. Current slows in a pool; making it easier to achieve a drag free drift without excessive mending. All pools contain three distinct zones – head, middle and tail. Many times, one side of the pool is shallow and the other deep. Eliminate the shallow side, plainly seen in this picture, to focus on the main current (red line).

At the head of the pool, there is usually a “shelf” created by the gouging action of the water. Trout will hold just downstream to avoid the initial turbulence; taking advantage of the pool’s depth while sticking close to the entering food.

The red lines in the picture below show the transition point (shelf) at the head of the pool followed by the primary current flow into the middle.

In deep pools, the current almost disappears; requiring additional cues. In the next picture, it is to the right of the floating leaves. If there were current on the left, it would push the leaves downstream. In still pools, look for very subtle moving indicators, like floating bubbles or small pieces of vegetation.

However, some pools may be exceptionally still, like this next one. Even in a quiet pool, attempt to guess where the current lies, using cues from the head and tail to fish along the extrapolated vector.

Sometimes, changing the viewing angle reveals the flow. From the upstream perspective in the picture below, it is easy to identify the edge of the current along the red lines and the possible feeding positions at the checkmarks.

The tail of the pool presents a unique problem (picture below). At this point, the current speeds up to push into the downstream riffle or run and concentrates the flow of food. Many times, the flow digs spots deep enough for the current at the bottom to slow within tolerance just above the transition line.

Riffles, runs, and pools – each hiding trout in secret spots. Suspend the urge to throw a quick first cast based on instinct and take the time to assess the situation. Find the current. Find the slicks. Find the channels. Decode hiding spots. Only when finished, consciously decide where the first cast should land.

While understanding the fundamental dynamics of current and depth will make a day on the stream more productive, this article barely scratched the surface. For better coverage of the topic, read at least one of the recommended books. Rosenbauer and Hughes are the ultimate experts who extend the conversation beyond the basics discussed here into what to use, how to use it and provide an understandable Ph.D. level discussion on how to pull trout from their hiding places. For example, this article only discussed what Hughes calls a “classic pool.” He decomposes pools even farther into bend, cliff, ledge rock, plunge and eddy pools while providing a recommended approach to dealing with each situation.